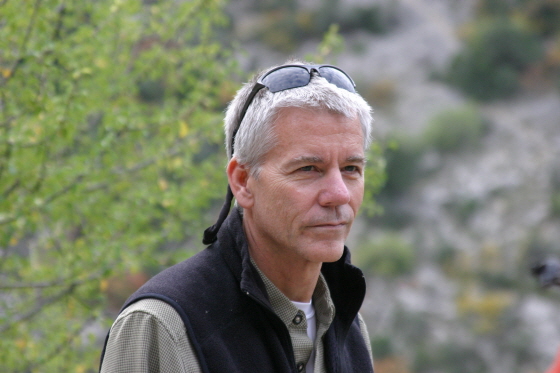

조경가 '키스 바우어스'와의 대담

"북한의 경관복원, 상당한 비용과 시간 들 것이다"

Q. 대학을 졸업하던 해에 바이오해비태츠와 ERM사를 설립하셨습니다. 학생 때의 어떠한 경험으로 인해 당신이 생태복원의 길로 들어섰으며, 여러 분야를 통섭하는 과감한 기업가 정신을 가능하게 했습니까?

A. 운이 좋게도 졸업을 앞둔 학기에, 메릴랜드주 연안에서 조수성 습지 복원에 대한 과학적이고도 예술적인 접근을 선도하고 있는 업체에서 일하게 됐습니다.

알도 레오폴드와 그의 후계 연구자들에 의한 미국 중서부 대평원지역의 복원 작업 이후, 지금 생각해볼 때 생태복원이라고 평가할 수 있는 일에 관여하고 있는 사람들은 극소수였습니다. 당시만 해도 대개의 환경운동 방식이란, 비영리단체가 사람들로부터 기부금을 모은 후 보존하고자 하는 지역의 땅을 매입해 개발을 저지하는 형태였습니다.

지금은 고인이 되신 에드가 가비쉬 박사(Dr. Edgar Garbicsh)가 이끌던 ‘Environmental Concern’이라는 기업은 조수성 습지에 대한 연구와 실험 그리고 가장 중요하게는 적극적인 복원 작업을 하고 있었습니다. 펄에서 코드그래스(cordgrass)등 다양한 습지식물의 파종과 번식을 실험하면서, 조류의 사이클이 습지 영양소의 순환과 에너지의 흐름, 식물의 천이에 미치는 영향을 깨닫는 중이었지요. 이 얼마나 멋진 일입니까! 강과 바다의 습지를 돌아다니며 놀면서 대자연과 지구 환경의 복원을 배우는 과정을 통해 돈을 벌 수 있다니요, 대단하지 않습니까?

저는 이 점에 완전히 매료됐고, 다행히 저를 이끌어주시던 가비쉬 박사라는 좋은 멘토가 계셨던 거죠. 생태복원이라는 분야에 관심을 갖기 시작할 때, 저는 생태학이라든가 일반적인 생물학 분야에 대해서 완전한 문외한이었습니다. 졸업이 임박했기 때문에, 그러한 과목들을 수강하는 것도 불가능했습니다. 저는 일단 학부 과정을 마치되, 볼티모어시 공원국을 위해 해안가의 조수성 습지를 복원하는 졸업 프로젝트에 심혈을 기울이기로 했습니다.

그런데 제가 연구를 진행하면서 알게 된 것은, 체사픽만(Chesapeake Bay)의 생태적 상황에 대한 많은 연구가 있음에도 불구하고, 이러한 과학적 정보들을 활용해서 어떻게 해안 환경을 복원할 것인지에 대한 실현가능한 방안이 거의 없다는 점이었습니다.

한편, 당시 조경설계나 인접한 건축, 엔지니어링 분야가 양산해내던 작업들은 오히려 체사픽만의 생태에 악영향을 주는 쪽이었지요. 사실 아직도 여전히 그렇고요. 저는 제가 갓 습득한 조경설계 기법과 과학적 연구를 쇠퇴하고 있는 생태계를 복원하는데 이용하자고 결심했습니다. 곧 응용생태학이지요.

어쩌면 당연하게도, 당시 조경학과 교수님들은 제 졸업프로젝트를 어떻게 평가해야 할지 몰랐습니다. 어떤 분은 저를 조심스럽게 사무실로 불러, 생태학 같은 곳에 시간을 허비하지 말고 좀 더 ‘디자인’에 집중하는 게 어떠냐고 조언하기도 했습니다. 제가 이 시간을 통해 배운 것은, 어떤 꿈이나 열정을 추구하기 위해서는 주위 사람들이 ‘너는 이래야 된다.’고 말하는 것을 무시하고, 스스로를 믿고 내가 옳다고 생각하는 길을 걸어가야 한다는 점이었습니다.

Q. 초창기 바이오해비태츠에 대해 말씀해주시겠습니까? 어떻게 다른 분야 전문가들과 함께 일하게 되었으며, 복원과 보전 분야에서 자리를 잡는데 결정적 계기는 무엇이었습니까?

A. 1982년도 졸업 직후에 곧바로 조경설계와 시공을 겸한 회사를 설립했습니다. 2년 후에 사업파트너의 지분을 모두 사들였고, 설계와 시공을 별도 회사로 분리해 바이오해비태츠와 ERM으로 만들었습니다. 바이오해비태츠는 보전계획, 생태복원, 재생디자인 분야를 위한 설계와 컨설팅 기업이었고, ERM은 그러한 생태 프로젝트들을 시공하고 사후 관리하는 역할이었습니다.

우선 저는 생태학을 적극적으로 조경에 적용하고 있는 설계사가 있는지 둘러보았습니다. 곧 깨닫게 된 것은, 안드로포곤과 같은 제가 존경하는 선구자적 소수의 업체가 생태적 원리들을 설계에 적용하고 있음에도 불구하고, 막상 지구과학이나 생물학을 전공한 타 분야 전문가들을 회사의 직원으로 고용해서 생태복원을 하는 회사는 없다는 것이었습니다.

그래서 저는 생태학자, 생물학자, 하천지형학자, 토양학자, 자연자원계획가, 토목학자, 프로젝트 매니저, 설비 운영자, 복원시공 감독과 일꾼들을 고용하고, 회계직, 오피스 매니저, 마케팅과 사업계획 수립 전담 직원 등을 갖추기 시작했습니다.

사업에 대한 경험이 전혀 없었기 때문에 금융과 자금운용, 미수금 계정, 채무 계정, 임금, 고용, 해고, 마케팅, 세일즈, 전산, 고객관리 등 회사 경영에 필요한 수많은 지식들을 빠르게 배워야했습니다. 회사 초기에 제가 했던 가장 현명한 일은, 제가 모르는 분야를 잘 알면서도 무엇보다 거기에 열정이 가득한 사람들을 언제나 주위에 둔 것이었습니다. 스킬은 책을 통해 쉽게 배울 수 있을지 모르지만, 열정과 패기는 가르친다고 배워지는 것이 아니기 때문입니다!

조경학 교육이 가르치는 것은, 아이디어와 생각, 컨셉들을 취해서 디자인 과정을 통해 랜드스케이프에 적용하는 것입니다. 반면 과학자들이 하는 일이란, 가설을 설정한 후 실험과 연구를 통해 새로운 결과를 발견하고 그것을 발표하는 것입니다.

저의 노하우라고 할 만한 것은, 디자인 아이디어가 아니라 과학자들이 하는 연구과정을 랜드스케이프에 적용해, 생태계 뿐만 아니라 그 땅에 살고 있는 사람들 모두에게 혜택을 주게 하는 방식을 알았다는 점입니다.

우리 회사는 곧 체사픽만의 스무 군데가 넘는 핵심지역에 대한 보전복원계획을 수립하는 사업을 발주했고, 볼티모어 내항을 가로지르는 해저터널, 포트 맥핸리 고속도로 상부의 조수성 습지를 11에이커에 걸쳐 복원하는 공사를 맡았습니다. 바이오해비태츠가 빠르게 성장할 수 있었던 배경에는, 토지이용계획과 부지설계를 표방하는 기업이면서도 그 기초를 생태과학과 이론, 연구에 두었기 때문입니다.

제가 처음 고용해야겠다고 생각한 사람들은 조경가가 아니라 생물학자, 생태학자, 지형학자였습니다. 그리고 실제로 많은 복원사업을 수주할 수 있었습니다. 의외로 아직도 미국에서 이러한 복합적 접근을 취하는 회사들 중 조경가가 대표를 맡고 있는 경우는 극히 드뭅니다.

ERM을 설립하면서는 자생식물 식재, 습지 복원이나 대체습지 조성, 토양의 바이오엔지니어링, 그리고 수질 향상을 위한 최적관리기법 분야에만 집중하자는 목표를 세웠습니다. 당시에는 이와 같이 전문화된 기업이 없었기 때문에 저는 바닥에서부터 시작해야 했습니다. 필요한 기술과 설비를 갖추고, 이러한 종류의 프로젝트를 수행하는 올바른 방법을 스스로 정립해야했죠.

바이오해비태츠와 ERM을 통해 우리는 고객에게 일괄발주 기회를 제공함으로써 복원사업에서 설계와 시공, 사후 관리까지 하나의 패키지로 묶었습니다. 당시에는 복원이라는 개념이 낯설었고, 디자인빌드라는 개념 또한 일반적이지 않았습니다. 설계와 시공을 통합하는 서비스를 통해서 고객의 필요에 잘 부합할 수 있었던 것은 사실이지만 더 중요한 점은, 응용생태학이란 학문은 전통적 사이언스와 달리 상당히 부정확한 과학(inexact science)이론이기 때문에, 실제로 무엇이 작동하고 무엇이 작동하지 못하는지를 검증해보는데 디자인빌드가 필수적이라는 사실이었습니다.

지금에 와서 돌이켜보면, 적절한 장소에서 적절한 때에 일을 시작한 것 같습니다. 1980년대 초반에 메릴랜드주는 체사픽만 수변에서 1000피트 이내에 위치한 모든 행정구역들에 대해서 체사픽만 핵심지역계획을 수립하도록 강제하는 법률을 통과시켰습니다. 때마침 미국 연방정부도 전국적으로 조수성, 비조수성 습지에 대해서 규제를 강화하여, 개발에 의해 습지가 훼손될 경우 대체습지를 조성하도록 했습니다. 당장 이런 일을 수행할 전문가와 자원을 갖춘 회사가 거의 없었다는 여건이 바이오해비태츠와 ERM를 자리잡게 도와주었습니다.

바이오해비태츠가 지금 수행 중인 작업에는, 뉴욕시 자메이카 베이 연안에서 굴초(Oyster Reef)와 홍합서식처, 수중식물을 설계하고 설치하는 작업, 콜로라도주 이그나시오강의 하천지형과 수생태계를 복원하기 위해 서던 우트(Southern Ute) 인디언 주민들과 공동으로 디자인과 커뮤니티 프로젝트를 수행하는 일, 장라피트국립공원(Jean Lafitte National Park)에서 미 국립공원청을 위해 수천 에이커의 습지를 복원하고 외래종인 중국오구나무를 제거하는 프로젝트 등이 있습니다.

연안에 거주하는 주민들과 협력하여 해수면 상승에 따른 식물군집에 생긴 변화와 종 서식처의 이동을 매핑하는 작업은 생태계 복원에 대한 조경적인 접근법이라 할 수 있습니다. 설립 이후, 바이오해비태츠는 미국과 해외에서 1천여 건이 넘는 생물다양성 복원 사업을 수행하였으며, 동시에 그곳에 사는 사람들의 삶의 질을 향상시켜 왔습니다.

Baltimore’s inner harbor

볼티모어 내항의 버려진 잔교를 활용해 생태적 수질 정화 장치 및 서식처를 제안한 계획

©Keith Bowers

Q. 설계와 시공 회사를 모두 운영하는 데 어려움이 있다면 무엇입니까?

A. 제가 두 회사를 설립할 때, 이 둘을 하나로 합칠 것인지 아니면 별도의 연관된 회사로 떼어놓을지 고민을 했습니다. 제가 도달한 결론은, 사업적 측면에서 볼 때 별도의 회사를 유지하는 것이 마케팅에서 유리하다는 것입니다. 각각의 전문성을 부각시킬 수 있고, 함께 하는 일 뿐만 아니라 각기 별도로 다른 설계나 시공 회사들과도 사업을 수행할 수 있기 때문입니다. 서로의 강점을 배우고, 경험과 지식을 공유하기 위해서는 반드시 한 회사의 지붕 안에 있을 필요는 없다는 생각이었습니다.

하지만 처음에는 무척 힘들었습니다. 하나의 회사를 만들고 운영하는 것도 보통 일이 아닌데, 일이 갑절이 되니 입에 단내가 날 정도로 힘들었습니다. 그래서 6년 후에는 ERM에 대표와 운영을 담당하는 두 사람의 최고경영자를 영입했습니다. 곧 바이오해비태츠에 최고운영관리자(COO)도 영입했구요. 이 두 번의 선택은 제가 30년간의 기업운영에서 가장 잘한 일이라고 생각하고 있습니다.

저는 현재 90%이상의 시간을 바이오해비태츠에 투자하며, ERM 경영을 두 분께 맡기고 있습니다. 그러면서 저는 회사의 전체적인 전략적 리더십을 수립하는데 더 많은 시간을 쓸 수 있고, 직원들의 멘토가 되고, 신사업기회를 개발하는 일에 주력할 수 있습니다. 그리고 경영 외 프로젝트의 일원으로서 직접 참여할 수 있는 여유도 주어지는데, 저에게 있어 이보다 즐거운 일은 없습니다.

설계와 시공을 병행하면서 가장 큰 장점은 서로에게 배울 수 있다는 사실입니다. 바이오해비태츠의 디자이너와 과학자들은 그들의 설계와 이론이 현장에서 작동하는지 실패하는지에 대한 직접적이고 즉각적인 실시간 피드백을 받습니다.

한편 ERM의 직원들은 복원생태학이나 자연지역 관리에 대한 가장 따끈따끈한 이론과 공법을 접함으로써 보다 수월하고 경쟁력 있는 사업을 수행할 수 있습니다. 여기서 난점은 두 회사 모두에 전적으로 관여할 수 있는 시간이 충분치 않다는 사실입니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 다행히 두 회사는 각각 핵심사업 부문을 성공적으로 안착시켜왔습니다.

Q. 생태복원과 보전계획 사업에서 조경가의 가장 중요한 역할은 무엇이라고 보십니까?

A. 제 생각에 조경가 훈련의 가장 큰 강점은 다양한 정보와 관점, 그리고 인식들을 ‘랜드스케이프’라는 통합적이고 협력적인 방법으로 구현한다는 점입니다. 말씀하신 두 분야 또한 현장에서 실제로 구현되기 위해서는 조경가가 다리를 놓아 그 중간 매개가 되어야만 합니다.

요즘에는 디자인에서 어떤 구역을 동식물을 위한 서식처로 설정하는 경우가 많은데, 막상 이러한 결정을 뒷받침하는 근거의 타당성에 대해서는 미심쩍은 부분이 많습니다. 어떤 목표 종을 왜 정했는지, 과연 그들의 필수적 생존 요소를 과학적으로 고려했는지에 대해서는 아무런 설명이 없습니다. 자칫 잘못 설정될 경우, 이러한 프로젝트는 동식물의 서식처가 아니라 해당 지역 희귀종의 멸종을 가져오는 유전적 무덤이 될 가능성이 있습니다.

저는 조경가들이 복원생태학, 보전생물학 그리고 경관생태학과 협력할 수 있는 최적의 지위를 갖고 있고, 과학적 연구를 통해 바람직한 보전정책을 정착시키며, 창의적으로 또 진정으로 지속가능하도록 경관에 적용하는데 유리하다고 봅니다.

다만, 피상적으로 한쪽의 희생을 강요하는 디자인은 바람직하지 않습니다. 생태계의 다양성뿐만 아니라 거기에 사는 사람들까지를 위하는 윈윈전략만이 우리 사회가 조경가에게 원하는 것입니다.

Q. 바이오해비태츠의 30년을 통해 당신이 조경의 관행적인 사고방식에 전해 온 사례에 대해 더 말씀해주시겠습니까?

A. 1980년대와 1990년대를 통해 저희는 미국 전역에서 생태복원 프로젝트를 수행하고 조수성 습지, 담수 습지, 이탄습지, 하천과 강, 활엽수림, 해안사구 등의 복원에 대한 전문가적 권위를 확립했습니다. 7곳의 생태지역사무소를 통해 북미와 캐리비안 도서지역, 그리고 국제적으로 프로젝트를 수행하고 있으며, 보전, 복원, 디자인 분야에서 100여 명의 직원이 연간 250여 건의 사업을 진행하고 있습니다.

약 12년 전쯤 이었던 걸로 기억합니다만, 저는 하나의 큰 변화 즉 융합현상을 감지했습니다. 이것은 그때까지 우리가 해오던 일, 그리고 새로운 환경운동의 흐름에 우리 자신을 위치시킬 것인가를 다시 생각게 한 큰 충격이었습니다. 쉘렌버거와 노드하우스가 “환경주의의 죽음”이라는 저작을 통해 말하려 한 바가 점점 더 설득력이 높아지고 있었습니다.

우선, 각 분야의 경계가 흐려지는 현상입니다. 말 그대로도 그렇고, 상징적인 의미에서도 그렇습니다. 최근에 나오는 Nature Conservancy(역주 _ 미국의 대표적 환경단체)의 브로슈어가 말하는 것은 더 이상 지구상 어떤 위대한 장소를 구하자는 구호가 아니라, 복원하고 관리하자는 메시지를 담고 있습니다.

그리고 이것은 더 이상 선택이 아니라 어쩔 수 없는 문제가 되었습니다. 주류 환경단체들의 공통된 인식은 우리가 더 이상 어떤 지역을 보존하려고 할 수만은 없으며, 적극적으로 복원하고 관리해야 한다는 것입니다. 광역적이고 전 지구적인 생태계의 변화로 인해 정해진 면적의 땅을 떼어놓고 보존을 도모한다는 의미가 많이 축소되었습니다. 겉으로는 매우 순수해 보이는 곳도 사실은 적극적인 복원 노력이 필요할 때가 많습니다.

토지계획이나 토목엔지니어링, 건축이나 조경에서 동일한 상황이 벌어지고 있습니다. 우리가 진정으로 지속가능하려면 생태계의 기능이 우리의 소비패턴을 제어하도록 해야 하고 그 후에 비로소 복원과 보전, 재생적 디자인이 제 역할을 할 수 있습니다. 기업의 경영이든 심리학이든 양자역학이든 커뮤니티 보건이든지 간에 점점 더 많은 증거들이 모든 것들이 서로 연결돼있다는 사실을 향하고 있습니다.

우리의 작업이 단순히 복원이나 보전에 국한된 경우는 이제 매우 드뭅니다. 오히려 강변의 수변서식통로를 복원하는 과정 못지않게, 그 강이 접하는 지역사회의 중심가를 활성화하는 전략 또한 저희 프로젝트의 핵심이 되고 있는 것이 그 예입니다. 경계가 흐려지는 현상은 더욱 가속화되고 있습니다.

둘째로는, 어떤 물질이 아니라 관계에 대한 것입니다. 저는 일하면서 과정보다 물질을 중요하게 생각하는 인식들을 느꼈습니다. 그것은 아마도 우리의 교육 시스템과 소비주의 문화에서 기인할 것입니다. 물질은 쉽게 인지할 수 있고 만질 수 있고 이해할 수 있습니다.

반면 과정이라는 것은 비가시적이고, 일시적이며 무한히 복잡한 것입니다. 예를 들어, 저희는 종종 빗물을 다루거나 멸종위기종의 서식처를 복원하는데 대한 최적관리기법을 개발해달라는 주문을 받습니다.

그러나 도시의 수문학이나 영양분의 순환이 어떻게 거리의 디자인이나 자동차공학과 상호작용을 하는지, 혹은 생물종의 라이프사이클이 광역토지이용 패턴이나 지화학적 과정에 의해 영향을 받는지에 대한 프로젝트는 거의 없습니다. 현재의 정치사회적 시스템이 어떻게 멸종위기종의 쇠퇴를 가져오는지, 또 그러한 쇠퇴가 어떻게 “서식처의 훼손”으로 나타나는지를 연구해달라는 요구는 없습니다.

이것은 현재의 지속가능성 운동에서 확연합니다. 건축가, 조경가, 엔지니어, 계획가들은 지속가능성을 “물질”의 견지에서 우리가 할 수 있는, 혹은 덜 할 수 있는 것을 고민함으로써 환경에 대한 부하를 줄이려는 고민을 합니다. 지속가능성이 지구상의 모든 생명을 지탱하는 생태적 과정과의 관계를 복원하는 것이 아니라, 단순히 덜 소비하는 것으로 환원되고 있습니다.

하지만 지속가능성은 물질에 대한 것이 아니라, 관계에 대한 것입니다. 다른 생명의 체계와 협동관계를 맺는 것이고, 우리가 생명의 진화에 참여하고 있다는 인식입니다. 그것이 우리가 재생적 디자인을 하는 이유이고, 생태적 과정과 인간과의 관계를 재생하자는 의미입니다.

저는 초기에, 생태복원이란 곧 과거의 복원이라고 생각했습니다. 과거 어느 시점 이후 경관에 남아있던 흔적들을 찾아내는 작업은 때로는 몇 세대, 몇 세기, 혹은 유럽인의 이주, 심지어 12,000전 후빙기 시기 이전까지 거슬러 올라갔습니다. 그러나 생태복원이란 오래된 자동차나 그림을 복원하는 일과는 다릅니다. 생태계의 복원은 과거 뿐 만이 아니라, 미래에 대한 통찰을 요합니다. 생태계는 끊임없는 변화의 상태에 있기 때문이며, 지구적 규모의 이변에 의해 변동하면서 투입과 산출을 조절하고 스스로를 새롭게 만들고 있기 때문입니다.

현재에 이르게 된 과정을 관찰하는 것은 필요합니다. 그러나 더 중요한 것은 앞을 내다보는 것입니다. 앞으로 변화된 상황에서 어떻게 복원을 실시함으로써 계속 번성하고, 발전하며, 다양성과 복잡성과 영화로움을 지속할 것인가 하는 문제입니다.

Anacostia River marsh before & after

워싱턴 D.C 애너코스티아강 습지의 복원 전후

©Keith Bowers

Q. 당신의 경험을 토대로 복원과 보전이 시급히 요구되는 이유가 무엇인지 설명해주실 수 있겠습니까? 프로젝트를 통해 기후변화나 해수면 상승 등의 영향에 대해 직접 느끼신 적이 있으신지요?

A. “우리는 연안 맹그로브 지대, 툰드라, 열대우림, 습지, 그리고 대양에 이르기까지 우리 주위의 모든 생태계가 붕괴되고 있음을 목도한다. 인간의 활동은 지구의 자연자원을 고갈시키고, 미래 세대를 지탱할 생태계의 능력에 의문이 생기고 있다.”

이것은 유엔이 1,300명의 과학자들의 도움으로 4년간의 연구를 반영하여 작성한 밀레니엄 에코시스템 어세스먼트가 경고하는 사실입니다. 우리는 자연의 다양성을 놀라운 속도로 소비한 후 폐기하고 있습니다.

스티븐 마이어는 그의 저서『The End of the Wild』에서 수십억 년의 생명체 진화는 점증하는 작은 규모의 힘, 혹은 우주적 스케일의 간섭, 즉 판의 이동이나 지구화학, 기후변동, 운석의 충돌 등에 의해 결정되어 왔다고 했습니다.

20세기 백 년 동안 이 모든 것이 변했습니다. 인간은 이제 가장 강력한 진화의 힘이 되었습니다. 상당한 규모의 행동을 통해, 그리고 수많은 매일 매일의 작은 행동들을 통해 우리는 의식하지 못한 채 지구의 식물들과 동물들의 운명을 결정하고 있습니다. 1980년대를 기점으로 인류의 자원소비량은 지구가 자연적으로 재생하는 양을 넘어섰다고 합니다.

이것은 우리가 생명과 지구를 지속하는 시스템에서 영원한 결핍을 겪게 됨을 의미합니다. 종의 멸종을 생각해보십시오. 지질학적 시간동안 지구는 고생태학에서 말하는 5번의 거대한 멸종을 겪어왔습니다. 많은 과학자들이 우리가 살고 있는 후빙기의 6번째 멸종을 경고하고 있습니다. 마이어에 의하면, 1억 년 동안의 속도로 미루어 볼 때, 일 년에 서너 종이 평균적으로 멸종한다고 합니다. 최근 연구에 의하면 현재 연간 약 3,000종이 멸종하고 있고 이 속도는 더욱 빨라지고 있습니다. 새로운 종의 출현은 1년에 약 1건 정도입니다.

이런 추세라면 2100년경에는 약 동식물 종의 반수가 사라지게 됩니다. 일군의 과학자들은 향후 90년간 일어날 절반의 종의 사멸에 비교할 때, 기후변화는 실제적으로 편리한 진실(convenient truth)이라고 주장합니다.

지난 100년간 미국은 세계의 보전활동을 이끌어왔습니다. 미국은 처음으로 국립공원을 설치한 나라이며, Henry David Thoreau나 Gifford Pinchot, Teddy Roosevelt, John Muir, Aldo Leopold와 같이 환경보전윤리의 창시자들이라고 할 만한 사람들을 배출했습니다. 또한 우리는 역사상 가장 엄격한 환경보전법을 가지고 있습니다.

그러나 우리는 실패하고 있습니다. 맑은 물, 깨끗한 공기, 건강하고 생산적인 토양, 기후 완화, 종의 다양성 등 모든 측면에서 우리의 자연 자원은 쇠퇴하고 있습니다. 기후변화와 깨끗한 담수의 부족, 그리고 종 다양성의 손실은 바이오해비태츠의 모든 프로젝트에서 결정적인 역할을 합니다. 조수성 염습지의 복원에서부터 우리는 해수면의 상승효과를 실감했습니다. 미래에 대한 복원은 이제 우리에겐 당위입니다.

Q. 복원 프로젝트가 어떻게 생태계의 탄력성과 경관의 질을 향상시킬 수 있습니까?

A. 이미 말한 대로 생태적 복원은 과거를 향한 복원이 아닙니다. 저는 이것을 “미래를 복원한다.”라고 표현합니다. 모든 생태계는 생체적이고 무생체적인 임계점의 경계 내에서 요동합니다. 이 임계점을 넘어선 생태계는 불안정해집니다.

대표적인 예가 중추종의 멸종이 랜드스케이프에 미치는 영향입니다. 늑대가 사라짐으로 인해 사슴 개체수가 예측할 수 없을 정도로 증가하는 것을 보아왔습니다. 사슴은 숲속의 모든 유목과 하부 식생층을 먹어치움으로써 숲 생태계를 파괴합니다. 영양종속(trophic cascades)라고 불리는 이 현상은 북미의 동부 활엽수림을 완전히 바꾸어놓아 매우 불안정한 경관을 초래했습니다. 보전의 노력과 생태복원을 통해 우리는 이 추세를 되돌리려는 시도를 하고 있습니다. 모든 복원은 탄력성을 복원하는 일입니다.

Q. ‘지속가능성’이라는 말에 대해 어떻게 생각하십니까? 재생적 시스템이라는 개념을 대안으로 제시하고 계신 건지요?

A. 지속가능성이라는 단어는 많은 경우 희석되고, 오용되어 왔습니다. 저는 우선 지속가능성이 지구와 사람과 이윤 사이의 균형이라고 하는 흔히 볼 수 있는 벤다이어그램을 지지하지 않습니다. 지속가능성이란 생태적 한계, 혹은 지구가 자연적으로 재생해낼 수 있는 범위를 넘어서지 않음을 말합니다. 우리가 현재의 소비속도를 유지하는 것은 지속가능성과 거리가 멉니다. 우리는 점점 지난 세대가 누리고 있던 종의 다양성에 대한 기억을 잊어버리고 있습니다. 생태적 기억상실증입니다. 남아있는 것들을 지속하자는 것은 좋은 출발점입니다.

그러나 우리는 그 이상을 요구받고 있습니다. 파괴되고 훼손된 생태적 과정을 재생하는 작업을 시작해야 합니다. 땅과의 관계, 상호간의 관계를 재생하는 것이 필요합니다. 우리가 재생적 디자인을 표방하는 것은 우리의 모든 작업에서 이러한 생태적 과정들을 재생한다는 의미입니다. 단순히 우리가 가진 것을 보전한다는 것은 충분치 않습니다. 복원을 말하긴 쉽지만, 진정 의미있는 재생적 디자인이란 매우 어렵습니다. 우리는 여전히 배우는 중입니다.

Baltimore’s inner harbor

볼티모어 내항

©Keith Bowers

Q. 다양한 분야의 협업을 통한 작업에서 느끼신 점은 무엇입니까?

A. 일단 무척 어렵습니다. 그리고 연습을 필요로 합니다. 그러나 그 결과는 무척 만족스러운 것입니다. 저는 우리가 다학문적이면서도 내향적인(Multi-intra-disciplinary)작업을 하고 있다고 말합니다. 우리가 넘나드는 다양한 학문들은 보전계획과 생태복원, 재생디자인이라는 중심축으로 수렴하게 됩니다.

이러한 과정을 성공적으로 이끄는 결정적 요인에는 두 가지가 있습니다. 바로 진실한 대화와 배우려는 분위기입니다. 진실한 대화란 요즘의 짤막짤막한 언어나, 지나치게 열정적인 외침, 혹은 승자가 모두를 취한다는 사고방식을 가지고서는 무척 어렵습니다. 경청과 감정이입, 충분히 근거있는 관점들을 필요로 합니다. 실상 우리가 어떤 문제의 답을 알고 있는 경우는 거의 없습니다.

그래서 저는 의도적으로 우리 회사를 배움을 추구하는 집단으로 만들었습니다. 여기서 우리는 우리의 성공과 실패와 무지함에 대해 솔직하고 투명하게 공개합니다. 이것은 우리의 적응적 관리(adaptive management)로 연결되는데, 적극적인 실험을 통해 과학을 경관에 적용하는 최선의 방안을 찾아간다는 의미입니다.

Q. 작년에 경관복원 전문가의 한사람으로 북한을 방문하신 적이 있지요? 뉴사이언티스트지에 그 경험담을 기고하셨는데, 심각한 처지에 놓인 북한의 경관을 복원하는데 우선시 되어야 할 점은 무엇이라 생각하십니까?

A. 북한 정권이 압제적이라는 점에 상관없이, 북한의 주민들은 도움을 절실히 필요한 상황입니다. 랜드스케이프는 바닥까지 채취되었으며, 황폐하게 남아있습니다. 이것은 단순히 생태적 재난이 아니라, 식량 안보의 재난이고, 환경정의의 재난이고, 종 다양성의 재난입니다. 북한의 랜드스케이프를 복원하는 데는 오랜 시간과 자금과 자원이 소요될 것입니다.

그러나 중요한 것은 그것이 가능하며, 또 반드시 해결 되어야 한다는 점입니다. 여러 가지로 서로 얽힌 문제를 풀기 위해 제 생각엔 두 가지의 복원이 우선돼야 한다고 봅니다. 첫째, 산림농업에 기반한 녹화사업인데, 여기에는 종 다양성과 토양안정화, 이산화탄소 흡수, 홍수 완화, 그리고 수질 향상 등 생태적 기능을 회복하기 위한 녹화사업과의 균형이 필요합니다.

이러한 녹화사업에 상당한 기술적이고 금융적인 자원이 필요하겠지만, 우선 북한에는 현재 유목의 번식과 재배, 운송을 위한 기본적인 인프라조차 결여되어 있습니다. 북한에 이런 모든 자원들이 부족한 반면, 유일한 인적 자원을 가지고 있습니다. 국제사회가 원조액의 일부를 지역 여건에 기반 한 총체적 녹화사업과 복원사업에 사용해야 한다고 생각합니다.

제 추정으로는 200~300억 달러 정도면 전 국토를 다시 녹화할 수 있다고 봅니다. 미국은 플로리다 에버글레이즈를 복원하는데 300억 달러를 사용하고 있고, 이라크와 아프가니스탄 전쟁을 위해서는 수천억 달러를 퍼붓고 있습니다. 북한 경관에 대한 복원은 단지 북한 주민의 식량안보에 관계될 뿐 아니라, 탄소 저감과 수질, 종 다양성을 위해 지구 어느 지역에 대한 복원보다도 중요한 일입니다.

북한을 개방된 사회로 만들기 위해, 또 독재정권이 붕괴되기 위해서는 사람들의 삶의 질이 향상되는 것이 절대적으로 필요합니다. 복원은 이러한 일을 실현할 수 있습니다.

Q. 당신이 생각하는 좋은 디자인이란 무엇입니까?

A. 좋은 디자인이란 무엇보다 생명을 주는 디자인이며, 생명을 가로채지 않는 디자인입니다. 좋은 디자인은 건강하고 활력있는 커뮤니티의 필요를 충족하면서도 자생적 종 다양성을 존중합니다. 그것은 재생적입니다. 그것은 매력적이며, 즐겁고, 영감을 주는 것입니다.

제 친구이자 동료이며, 뉴멕시코 산타페에서 퍼머컬쳐를 행하고 있는 팀 머피의 충고는 경청할 만한데, “온갖 종류의 호혜성을 만들어내는 만남에 참여하는 것”이 그의 대답입니다.

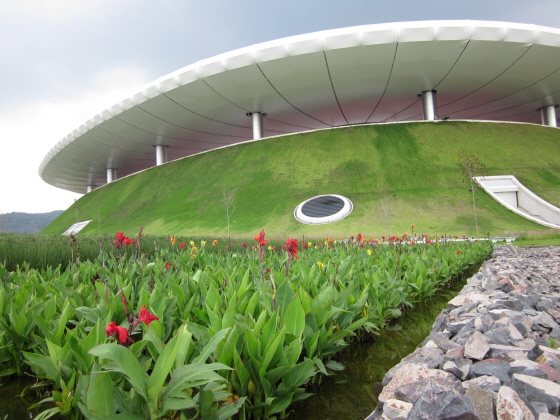

Mexico Estadio Omnilife

멕시코 옴니라이프 스타디움에 하수정화를 위한 인공습지 조성

©Keith Bowers

Keith Bowers

Q. You founded Biohabitats and ERM in the year you graduated from West Virginia University. What experience as a student led you to the world of ecological restoration and multi-disciplinary entrepreneurship?

A. Fortunately, while in my senior year of the Landscape Architecture program, I came across a firm on the Eastern Shore of Maryland that was pioneering the science…and art of tidal wetland restoration. Except for the work that Aldo Leopold and others that followed him did on the restoration of prairies in the mid-West, only a handful of people at the time were engaged in what we now know as ecological restoration. Up until this time, the primary means in which people participated in the environmental movement was to give money to a conservation organization that bought and protected land. Now, here was firm called Environmental Concern, lead by the late Dr. Edgar Garbicsh, that was researching, experimenting, and most importantly actively restoring tidal marshes – in the mud, propagating and planting smooth cordgrass with a variety of other species, learning about the tidal cycles and their affect on nutrient cycling, energy flows and plant succession. How cool was this! Someone was getting paid to play in the marsh, be outside on the water, learn about nature and restore the earth, all at the same time.

I was sold, and more importantly I had a mentor. I started looking into this field called ecological restoration. As I did, I discovered that while it was in its infancy, I had absolutely no training in ecology or for that matter, the life sciences. As I was about to graduate, it was too late for me to begin taking electives in biology and ecology. I finished out my undergraduate with a capstone project that focused on restoring a peninsula and two adjacent tidal creeks for the Baltimore County Department of Recreation and Parks.

I soon discovered that there were many scientific studies and research being conducted on the state of the Bay's ecology, but little was being done to take this information and actually apply it in a practical way to help restore the Bay. And, to make matters worse, many of the land use practices that landscape architects and other design professions were engaged in (and in many respects still are) were actually contributing to the degradation of the Bay’s ecosystem. I began thinking about how I could apply my newly minted landscape architecture skills in a way that took the science and applied to the landscape to restore ecosystems that were on the decline - the idea of 'applied ecology'.

Needless to say my professors did not know how to technically evaluate my project. In fact one of them brought me into his office, suggested that I refocus my efforts on ‘design’ and not waste my time on ecology. One of the first lessons I learned was that in order to follow your dream… your passion, you have to ignore what others think you ought to do and trust within yourself that you are on the right path.

Q. Could you describe the early days of your practice? How did you start working with other experts? What was the breakthrough moment that established your firm in the field of restoration and conservation?

A. I graduated and immediately started a landscape design and construction firm. Within two years I bought out my partner’s shares of the company, split up the design and construction arms into two separate companies; Biohabitats and Ecological Restoration and Management, Inc. Biohabitats would be the design and consulting firm focused on conservation planning, ecological restoration and regenerative design, while ERM would be the contracting and management company that built and managed these ecological projects.

I looked around for other landscape architecture firms integrating ecology into their practice. What I very quickly realized is that while there were some firms that incorporated basic ecological principles into their work (Andropogon being a leading example and a firm I greatly admire), none of these firms were practicing ecological restoration and none of them employed people with earth and life sciences backgrounds.

This led me to begin hiring ecologists, biologists, fluvial geomorphologists, soil scientists, natural resource planners, civil engineers, project managers, equipment operators, restoration foremen and crew, accountants, office managers, marketing and proposal folks, etc.

With little to no business background, I quickly learned about finance, cash-flow, accounts receivable, accounts payable, payroll, hiring, firing, marketing, sales, computers, customer satisfaction and…well the list goes on and on. One of the smartest things I learned early on was to surround myself with people who knew what I didn’t know and who had a passion for what they did. You can teach skills; you can’t teach passion and drive!

What I have also come to learn about my landscape architecture education is that it taught me how to take ideas, thoughts, and concepts…and apply them to the landscape. Scientists are trained to develop a hypothesis, conduct research, evaluate their findings and publish their results. The trick, I soon learned, was how to take their work and apply it to the landscape in a way that benefits both the ecosystem and the people who interact with the land.

Quickly winning commissions to prepare over two dozen Chesapeake Bay Critical Area plans and winning a contract to restore 11 acres of tidal marsh overtop the Fort McHenry interstate highway tunnel under Baltimore’s inner harbor, Biohabitats was rapidly underway as a firm grounded in solid land use planning and site design but built on a foundation of sound ecological science, theory and research. I also recognized very quickly that my first hires needed to be biologists, ecologists and geomorphologists in order to undertake the work we were winning. To my surprise, there were very few, if any firms in the U.S. that had a multidisciplinary approach and were led by a landscape architect.

My initial goals with ERM were to focus exclusively on native landscape planting, wetland mitigation and restoration, soil bioengineering and water quality best management practices. Recognizing that there were no firms like this in the US, I had to build ERM from the ground up, establishing the necessary skills, specialized equipment and knowledge to implement these types of projects. An advantage of establishing both Biohabitats and ERM was the opportunity to offer clients a turnkey package for designing, implementing, and managing restoration projects. Like restoration, the idea of employing design-build services was a new and evolving procurement method, however given the inexact science of applied ecology, I saw the utility of combining design and construction services to better serve clients and more importantly, learn firsthand what was working and what wasn't.

Looking back, being at the right place during the right time really helped. In the early to mid 1980's the state of Maryland passed legislation regulating all jurisdictions that governed land around within one thousand feet of the Chesapeake Bay to develop a Chesapeake Bay Critical Area Plan. Concurrently, the U.S government began enforcing laws protecting tidal and non-tidal wetlands throughout the country, requiring impacts to these wetlands to be mitigated by restoring degraded wetlands. There were very few firms that had the expertise or resources to take this type of work. This work helped launch Biohabitats and ERM.

Biohabitats is now working with New York City to design and install oyster reefs, mussel beds and submerged aquatic plant demonstration projects in Jamaica Bay; collaborating with the Southern Ute Indian Tribe in southern Colorado to design and implement community projects to restore the morphology and aquatic ecology of Ignacio Creek; removing invasive exotic Chinese tallow trees and restoring tidal flow to thousands of acres of marsh for the National Park Service at Jean Lafitte National Park, partnering with coastal communities to identify and map changes in plant community ecology and species migrations due to sea level rise associated with climate change, to exploring the ways in which the attributes of landscape architecture are embed in ecosystem restoration. Biohabitats has participated in over 1000 projects throughout the United States and abroad to restore biodiversity while bettering the livelihoods of people and the communities they live and work in.

Q. What are the advantages and difficulties of running both design and build companies?

A. When I established Biohabitats and ERM, I gave much thought about whether I wanted a firm that included both design and construction services or whether to establish two separate but related firms. I came to the conclusion that from a business development perspective, having two separate firms that could market their respective expertise and pursue work that may be associated with other design or construction firms made the most business sense. And at the same time we could still pursue design-build work and learn from each other's strengths, experience and knowledge. At first it was very challenging. Establishing one business is hard enough but two is very challenging. So I decided after about six years to hire two people to lead and operate ERM. Shortly after I also decided to hire anchief operations officer for Biohabitats. These were two of the best business moves I have made. I now spend about 90% of my time with Biohabitats, while my two partners in ERM operate that company. I now have far more time to provide overall strategic leadership, mentoring and business development. It also lets me spend more time working on projects, the really fun work.

I would say that the primary advantage of operating design and build companies is the opportunity to learn from one another. In Biohabitats, designers and scientists get direct and real-time feedback on what works and what doesn't in the field. Conversely, ERM has access to the latest theories and applications in restoration ecology and natural lands management, which they can incorporate into their work. The difficulty always lies in finding enough time to stay fully engaged with both firms simultaneously. Luckily we have built a good business core within each organization that allows both firms to prosper.

Q. What would be the critical role of landscape architects in the projects of ecological restoration and conservation planning?

A. I believe landscape architects are well trained in how to apply a diversity of information, perspectives and perceptions to a landscape, in a collaborative and inclusive way. Landscape architects play a vital role in conservation planning, ecological restoration and regenerative design in bridging the science of these two disciplines with their on-the-ground applications. We see many landscape architects designate open space as habitat for native flora and fauna, without having any scientific underpinning in terms of what species it is targeting, what are their life requisites, or whether it might even serve as a genetic sink that would lead to the ultimate extinction of a suite of species within that area. I believe landscape architects are in a perfect position to work collaborative with restoration ecologists, conservation biologists and landscape ecologists in taking the scientific research that support good conservation practices and finding ways to creatively apply them to the landscape in a truly sustainable manner. Trade-offs are not an option. We need landscape architects that find win-win solutions for both people and biodiversity.

Q. In 30 years of practice since 1982, how have you challenged the conventional way of thinking in landscape architecture?

A. Through the late 1980’s, 90’s, we took on a variety of ecological restoration projects throughout the country, gaining a national reputation for restoring tidal marshes, freshwater wetlands, bogs, streams, rivers, deciduous forests, and coastal dunes, among others. Throughout our 7 bioregion offices, our work now spans North America the Caribbean, and internationally. Between both companies we employ well over 100 people providing conservation planning, ecological restoration and regenerative design services to more than 250 projects a year.

About 12 years ago I began to sense a change…a convergence really. convergence that shook my understanding of what we were doing and how it fits within the context of the current environmental movement. A convergence that made me think that maybe Shellenberger and Nordhaus have it right with the Death of Environmentalism.

First, there is, what I call, the Blurring of the Boundaries. I mean this both figuratively and quite literally. If you pick up one of The Nature Conservancy’s brochures, what you notice now is that they are not just about conserving the last great places on the planet; they are also now about restoring and managing them. We have no choice - we have to. Mainstream conservation organizations have come to the conclusion that we can’t just protect land, we need to actively restore and manage this land. With both regional and planetary changes to our ecosystems, conservation, or setting land aside, is not good enough anymore. We must take an active role, even when sites ‘look’ pristine. I have also noticed this same trend taking over the land planning, civil engineering, architecture and landscape architecture professions. Clearly, if we are going to be truly sustainable, that is letting ecosystem function dictate our consumption patterns, then both restoration and conservation and what we term, ‘regenerative design’, have a major role to play. Whether it is corporate management, psychology, quantum physics or community health, the evidence is mounting that everything is connected…in profound and sometimes startling ways.

Rarely does our work anymore focus exclusively on restoration or conservation. To the contrary, our work now is as much about revitalizing a community’s town center as it is about restoring a riparian corridor along its riverfront. Blurring the boundaries is happening at an accelerating rate.

Secondly, it’s about relationships, not stuff. Throughout my career I have come to notice that ‘things’ take precedent over processes. Perhaps this is a legacy of our education system and our consumer-based societies. Perhaps because things, or ‘stuff’ are easier to see, easier to touch and easier to comprehend, than processes or relationships, which are at times invisible, temporal and infinitely complex. In our practice we are often asked to develop best management practices to treat stormwater, or restore habitat for an endangered species, but very rarely were we ever asked to explore how hydrologic and nutrient cycles interact with urban street design and automotive engineering, or how species life-cycles are influenced by regional land use patterns and geochemical processes. It is even more rare that we were asked to explore how socio-political systems may be responsible for the precipitous decline of an endangered species and how that decline has physically manifested itself in terms of ‘habitat degradation’. This is really evident in the current sustainability movement. Many architects, landscape architects, engineers, and planners view sustainability in terms of ‘things’ we can do, or do less of, to reduce the burden we place on the environment. As if sustainability is about consuming less instead of about restoring our relationship with nature and the myriad of ecological processes that support life on this planet.

No, it is not about stuff, it’s about relationships. It’s about participating in a partnership with other life systems, awareness that all things are connected and that we are co-participants in the evolution of life. That is why we practice ‘regenerative’ design, regenerating ecological processes and human relationships.

When I first started practicing ecological restoration, I came to recognize it as a way of restoring the ‘past’. That is, restoring some relic landscape that existed at some point in the past, perhaps a generation ago, perhaps a century ago, perhaps prior to European settlement, or maybe at the dawn of the Holocene era 12,000 years ago. But unlike restoring a vintage automobile or a masterpiece painting, restoring an ecosystem requires us to think not only about the past, but far into the future. Ecosystems are in a continuous state of evolution, responding to planetary events, adjusting to their inputs and outputs, and remaking themselves over and over again. Yes, we need to look back in time to make sure we understand the processes that got us to this point, but more importantly we need to look forward. We need to figure out how to restore ecosystems so that they will persist…and more importantly evolve, with all of their diversity, complexity and splendor; while at the same time sustaining us in mutually beneficial ways with all of the world’s species.

Q. From your experience, could you explain for design students and professionals the urgent need for restoration and conservation? Have you encountered the effects of climate change and sea-level rise in the course of your career?

A. All around us we are laying witness to the collapse of major ecosystems throughout the globe including coastal mangroves, arctic tundra, tropical rainforests, wetlands, and now oceans, to name only a few. Human actions are depleting Earth’s natural capital, putting such strain on the environment that the ability of the planet’s ecosystems to sustain future generations can no longer be taken for granted warns the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, a four-year study sponsored by the United Nations and published about three years ago with the help of over 1,300 scientists.

Bit by bit we are extracting, exploiting, consuming and discarding earth’s natural diversity at an alarming rate.

Stephen M. Meyer, in The End of the Wild, has reminded us that for billions of years evolution on earth has been driven by small-scale incremental forces (Darwin’s survival of the fittest), punctuated by cosmic scale disruptions (like plate tectonics, planetary geochemistry, global climate shifts, perhaps asteroids). Sometime in the last century, all of that changed. Humans are now the driving force behind evolutionary change. Think about that… through some fairly sizable acts, but mostly through billions of small every-day actions, we are now unknowingly controlling the fates of most of the world’s plants and animals. In fact, since the 1980’s humans have been consuming more resources than the earth can naturally replenish. That means we are in an ever-increasing deficit with the very systems that supports life, our life, on this planet.

Consider species extinction. Over geologic time, the earth has gone through what paleoecologists call 5 great extinctions. Now, many scientists are warning us that we are experiencing the 6th Great Extinction- the Holocene Extinction.

Meyer reminds us that the fossil records and current studies suggest that the average extinction rate of the past 100 million years has averaged about several species per year. Today, the extinction rate exceeds 3,000 species per year…and is accelerating. In contrast, new species are appearing at the rate of about 1 per year. Given our current course, one-half of all plant and animal species will go extinct by 2100.

Some might argue that climate change is actually the ‘convenient truth’ compared to the unimaginable and permanent loss of 1/2 of the earth’s species within the next 90+ years.

Over the past 100 years the US has led the world in conservation. We were the first nation to establish a National Park System; we gave rise to the likes of Henry David Thoreau, Gifford Pinchot and Teddy Roosevelt, along with John Muir and Aldo Leopold who are considered by many to be the fathers of our current conservation ethic. We have some of the most stringent environmental protection laws in the history of the world, yet we are failing. Our natural capital – those ecosystem processes that we take for granted like clean air, fresh water, healthy productive soils, climate regulation, species diversity, are all in precipitous decline.

Climate change, scarcity of fresh water, and loss of biodiversity play critical roles in all of the projects we work on. We have seen first hand sea level rise effects on much of the tidal salt marsh restoration and oyster reef restoration projects we are involved with. Restoring for the future is a must for us.

Q. Could you explain how a restoration project enhanced the performance and resilience of an ecosystem and the quality of the landscape?

A. Ecological restoration projects inherently enhance the performance and resilience of an ecosystem and the quality of the landscape. Ecological restoration is not about restoring an ecosystem to a condition that existed in the past. Rather it is about restoring an ecosystem to future conditions. I call this ‘restoring the future’. All ecosystems vacillate within biotic and abiotic threshold boundaries. When an ecosystem begins to cross over one of these threshold conditions, it becomes inherently unstable. A good example is the loss of keystone species (e.g. wolves) on the landscape. In the wolf example, without predation we are witnessing an extraordinary increase in deer populations, which in turn are devastating forests by grazing on all of the understory and young-of-year trees. This cascading effect (called trophic cascades) is completely changing the eastern deciduous forest in North America, creating a very unstable landscape. Through conservation initiatives and ecological restoration we can begin to reverse these affects and restore the landscape to robust, healthy and resilient forest. Inherently all restoration should work toward restoring the resiliency to ecosystems.

Q. What do you think of the term sustainability? Would you describe the concept of regenerative systems as an alternative?

A. The term sustainability has become watered down and in many cases misused and abused. First off, I do not support the way sustainability is characterized as a balance between planet, people and profit, the ubiquitous Venn diagram. Rather for us, it is first and foremost about not exceeding the ecological limits, or ‘footprint’ of the earth’s ability to naturally regenerate resources. Scientists have concluded that since the 1980’s we are living beyond the capacity for the earth to regenerate the stock of resources that we are consuming. In other words, sustaining what we have left, or sustaining our current rate of consumption will not make us truly sustainable. Do we really want to sustain what we have left? From generation to generation we tend to slowly forget the rich diversity of life that we had during the previous generation- ecological amnesia. Sustaining what is left is a good start, but we must do more. We must begin regenerating ecological processes that have been damaged, degraded and destroyed. And we need to regenerate our relationship with the land and with each other. We purposively practice regenerative design because we believe we need to reestablish our relationship with nature and to regenerate ecological processes in everything we do. It’s just not enough to sustain what we have. The real trick, and challenge, is to practice regenerative design that is truly meaningful. We are still learning.

Q. What are some lessons to be learned from the multi-disciplinary practice?

A. It’s hard, it takes practice, and it’s remarkably rewarding. I would say we practice a multi-intra-disciplinary practice. It both encompasses many disciplines centered on the disciplines of conservation planning, ecological restoration and regenerative design. I would say there are two keys to making a multi-intra-disciplinary approach work; true dialogue and a learning culture. True dialogue is hard to come by in today’s world of sound bites, impassioned rants and a winner-take-all attitude. It requires listening, empathy and informed perspectives, which brings us to a learning culture. We don’t know all of the answers, in fact very few. So we have purposively established a learning organization, where we are transparent about our successes, failures and unknowns. In essence, this leads us to practice adaptive management, where we actively test and seek out the best ways of applying science to the landscape. Most of all it is fun interacting with people that bring different perspectives, skill sets and impassioned energy to a project.

Q. You visited North Korea as an expert of landscape restoration early last year and wrote an article in New Scientist magazine depicting the extreme conditions of poverty and a repressive regime. What are the priorities for the restoration of the severely degraded North Korean landscape?

A. Putting aside the repressive regime of the DPRK government, the people of North Korea need help. They are living in absolute poverty, the worst kind. Their landscape has been scraped and laid barren. This is not only an ecological crises, it is also a food security crises, an environmental justice crises and a biodiversity crises. Restoring North Korea’s landscape will take time, resources and money, but it can – and should – be done. To address these interrelated challenges, two types of restoration should be given priority; revegetation based on an agro-forestry program balanced with revegetation to support a variety of ecosystem functions including biodiversity, soil stabilization, carbon sequestration, flood attenuation, and water quality improvement, to name a few.

This will take considerable effort. In addition to the technical and financial capital required to undertake such a program, North Korea also lacks in the basic infrastructure to propagate, grow and transport large numbers of seedlings. While North Korea is deficient in many of the resources needed to fully restore their landscape, they do have the human capital to make it happen. If the international community would begin redirecting a portion of their foreign aid to North Korea toward a comprehensive place-based initiative for reforestation and restoration the county and it’s people would benefit for generations to come. I would suspect that $20-30 billion dollars could reforest the entire country. The US is spending $30 billon on restoring the Florida everglades and we know that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have cost $100s of billions of dollars. Reforesting the country would not only provide food security but also benefit the planet in terms of carbon sequestration, water quality and biodiversity. In order to ‘open’ up this society, and to have any hope that the political regime will collapse, people's livelihoods need to be improved, and restoration can make that happen.

Q. What is good design?

A. Good design for me first and foremost is life giving, not life taking. It respects native biodiversity while providing for the needs of healthy and robust communities. It is regenerative. It’s also engaging, fun and inspiring. We will be well served to heed the advice of my friend and colleague, Tim Murphy, a permaculturalist from Santa Fe, New Mexico, who, when asked what makes good design, he is fond to reply, ‘engage in a riot of reciprocity”

- 공동글 _ 박명권 · 그룹한어소시에이트

-

다른기사 보기

lafent@naver.com

- 공동글 _ 최이규 · 그룹한어소시에이트

-

다른기사 보기

lafent@naver.com

기획특집·연재기사

- · "안정적 공원운영? 민관파트너십 통한 예산확보로"

- · 주목할만한 조경가 12인_벤자민 돈스키

- · "정원디자인, 시간의 흐름을 따르는 연주"

- · 주목할만한 조경가 12인_피엣 우돌프

- · "디자인에서 진정성은 항상 중요해"

- · 주목할만한 조경가 12인_케빈 콘거

- · "옴스테드 디자인철학, 여전히 유효하다"

- · 주목할만한 조경가 12인_비톨드 립친스키

- · "건물을 넘어, 도시 규모로 확대되는 버티컬 가든"

- · 주목할만한 조경가 12인_패트릭 블랑

- · "걷기좋은 도시는 국가를 부유하게 만든다"

- · 주목할만한 조경가 12인_제프 스펙

- · 주목할만한 조경가 12인_키스 바우어스